How Can We Help?

What Happens During a Ledger Fork?

Forking is a phenomenon that occurs in all cryptocurrency networks. However, all cryptocurrency networks are not equally resilient to forks nor do they handle forking the same way. There are also different types of forks. (Here's a succinct overview of forks.)

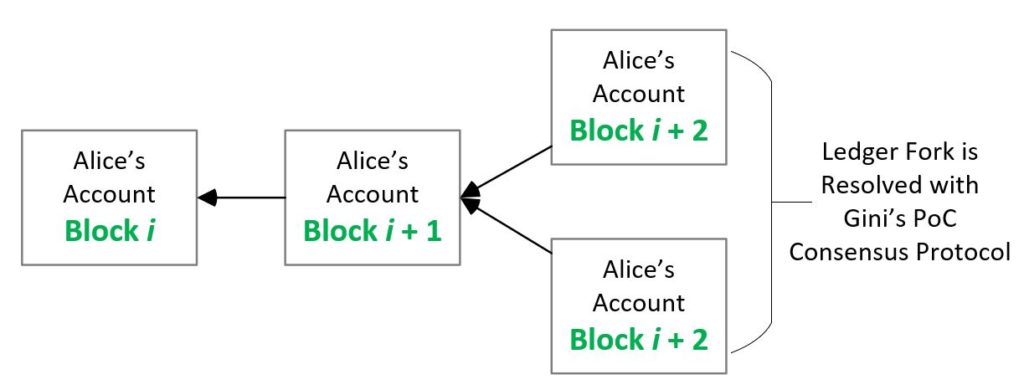

In this case, we're talking about a specific kind of fork that we call a "ledger fork". A ledger fork occurs when two blocks point to the same parent block. The diagram below illustrates a ledger fork and the animation on the Gini Trust Protocol page illustrate how forks are resolved on the Gini Network.

A ledger fork creates a temporarily ambiguous ledger state until a cryptocurrency's consensus protocol resolves the fork. Depending on the cryptocurrency network in question, a ledger fork may exist for less than 1 second or it might exist for much longer. While the ledger is forked, the network is vulnerable to several kinds of attacks. So, it's important for a cryptocurrency to be inherently designed to be as resilient to forking as possible.

On the Gini Network, only an account’s owner (“Alice” in the diagram above) can sign blocks into their private blockchain, which is logically synced to the global Gini BlockGrid ledger. Thus, unlike other cryptocurrencies where ledger forking happens frequently (multiple times per day) as an unavoidable byproduct of the way their blockchains are designed, a ledger fork can only occur on the Gini Network in very rare cases, e.g., when a node is malfunctioning or acting maliciously by deliberately trying to execute a double-spend attack.

Since Gini nodes are engineered to the highest standards humanly possible, the most realistic way that a ledger fork might theoretically occur on the Gini Network is from a malicious hacker who modifies their own copy of their Gini node software to see if they can force it to inject fraudulent transactions into their local ledger before it's synced to the global ledger. Even though this is theoretically possible, given Gini's unique architectural BlockGrid design, the damage that such a hacker could cause would be limited to their own account.

It's theoretically possible that this kind of attack could impact one of the hacker's own direct counterparty accounts under a very specific and unrealistic scenario: The hacker would need to hack his copy of the Gini software, then quickly fork his local copy of his private account ledger, then execute a double-spend attack against his own counterparty, and his own counterparty would need to be blind to being rushed into such a fishy transaction. Additionally, all this would need to occur in a fraction of a second before the hacker's local private account ledger copy was synced to the global ledger. (Of course, this is a highly unrealistic scenario, but we share it to illustrate how extremely difficult it is to hack the Gini Network.)

Regardless, in all real-world cases, the hacker could never impact anybody else on the Gini Network because the Gini BlockGrid compartmentalizes each stakeholder's private account blockchain from all the other private account blockchains on the network. That's why Gini is much more resilient to forking and many types of attacks compared to other cryptocurrencies.

Did You Like This Resource?

Gini is doing important work that no other organization is willing or able to do. Please support us by joining the Gini Newsletter below to be alerted about important Gini news and events and follow Gini on Twitter.